A review on “Little Soldiers” by Lenora Chu.

I have gone through the book in the title. I am no saying “have read”, because for quite some time already, since first grasping this trick while conquering Baudrillard’s “Simulacra”, I am getting through a lot of material via listening to Text-to-Speech, rather than reading directly. Not just is it very handy when there is a “sunken” time during which it is not possible to execute tasks that require full concentration. This, however, comes at a price, namely, certain details are perceived differently, compared to reading in a traditional way.

Anyway, I have listened through the book, and it was an enlightening experience, which I would like to share with the world in this short review.

The book tells a story of an American couple with two children living in Shanghai for a few years, who’s elder son had a chance to attend classes in a Chinese kindergarten (as opposed to what typically happens to the expat children in China – they attend foreign-style kindergartens, which are especially plentiful in Shanghai).

The book was especially interesting to me, as I am not an original product of either American, or Chinese culture, so I had a chance to see the story from a third-party perspective.

1. The Review

1.1. Author

I have to say in advance, I have read this book in Russian, rather than in the original English. I generally read in English quite a lot, however, I didn’t bother finding an English version when I had already found a Russian one I don’t remember where from. (It was on my reading list for quite a while.)

Mrs Chu herself is, or at least used to be, (2017) the chief of an American non-profit organisation Shanghai office. She is a child of Chinese migrants to the United States, and hence had an opportunity to experience both American and Chinese influence in her upbringing.

She is also a member of the American council on relations with China: https://www.ncuscr.org/program/public-intellectuals-program/PIP-VI-fellows/lenora-chu

This immediately made me wonder where is the Russian Council on Russia-China relations. Of course, there is a Russian Council on Foreign Affairs, but it is hardly a substitute.

1.2. Synopsis

The book starts with her choosing a kindergarten for her kid. She is contemplating between a foreign-style kindergarten and an authentic Chinese one.

Obviously, curiosity wins over, and she arranges him joining “the most sophisticated Chinese kindergarten in Shanghai”, supposedly, the one which is attended by the cream of the crop of the Shanghainese elite.

As grown-ups, we all know how important is the environment in which we are spending our time. Even if we are not learning anything, or deliberately changing ourselves in some planned way, the surrounding conditions influence us. And even if your child is investing strenuous effort into not learning anything at all from the teachers he is made to obey (which is unpredictable, and beyond the parent’s influence), the environment is going to have its effect regardless, and thus choosing a school is, perhaps, the most powerful way to shape your kid’s future, second only the effect of your own behaviour, which the child is bound to imbibe just due to being your offspring.

It is often noticed (at least in Russia), that the most prestigious and competitive universities are, surprisingly, not the ones which have the best programmes or best teachers, but rather the ones which are chosen by the elites as schools for their children. Needless to say, the strongest weak connections, and those that are the most likely to help you as you progress into your life, are the ones created while attending a University.

It is questionable, however, whether this paradigm applies to kindergartens as well, rather than existing as a projection of an adult way of behaving onto little children. Personally, I only remember three people I have attended a kindergarten together with, and keep in touch with none of them.

However, this projection of adult fears onto the children’s lives goes through the whole book as a guiding light, and appears in so many places that it could, perhaps, even be promoted to a second title of the book.

1.3. Content

The book is roughly consisting of two parts: the events in the life of Lenora’s child, and how these events are actually particular cases of general trends in the Chinese society.

Competitiveness, poverty, fear of the future, rapid changes, foreign influence, corruption, migration – each of these things occupies a separate chapter in the book, and each of these chapters is started with a sketch of a situation happening with Lenora’s kid.

She has done a great deal of background research while writing the book – both studying the existing body of knowledge, books, newspapers, and doing fieldwork – interviewing people, studying real events, and engaging in social mechanisms (such as parents’ groups).

The language she is using is very vivid and clear. I could almost effortlessly imagine the scenes of events happening in the book. Granted, I have seen quite a lot of China, and especially Shanghai, so I probably can understand the situations better than an average foreigner reading about events so distant.

1.4. Competition

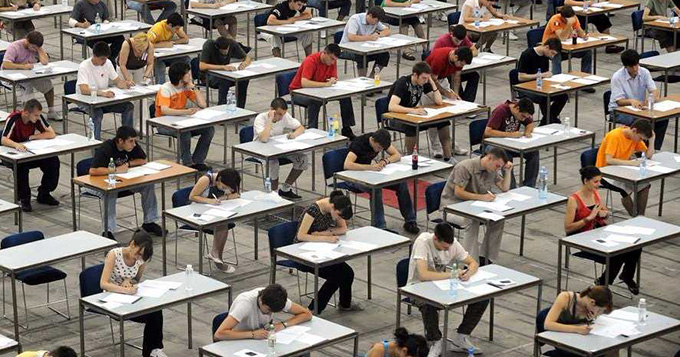

China is a very competitive society.

When I was a kid, it was widely believed by people around me that the USA is the best example of a competitive society, and that Americans do not have the concept of friendship at all. In general, there were a few rumors about American life, widely circulating in the society, that were deemed to illustrate the degree to which Americans are cold-blooded, self-centered, merciless people completely devoid of spirituality, that are going to trade you in for a tiny benefit for themselves.

Those rumors included:

- Singing company’s anthem in the morning.

- Team-building events aimed at capturing your soul and stealing your free time.

- Medals and honorary certificates given to you by your company as bonuses (instead of cash).

- Absolute obsession with money.

- Obsession with winning at all costs.

- Complete dependence of waiters on tips instead of a fair salary.

- No holiday leave or maternity leave.

Can you imagine my surprise when I experienced almost all of that in China after I had come here for work? (The largest item missing from this list is tips. Tips are not used in China, and thank God for that. Tips are a complete insanity.)

However, Mrs Chu, who can compare the competitiveness of the two societies first-hand, is surprised by the amount competitiveness too.

She acknowledges that American society is fairly competitive, but Chinese level is surprising even for her.

She even gives a plausible explanation – Chinese society has grown significantly and very quickly in the last generation’s lifetime. People also largely attribute this growth to the education system, and hence want to ensure a better future for their children, and keep pushing them to achieve.

The problem here is that, even though the country has grown, not all industries have grown at the same pace. Naturally, some have a physical limitation on them. Education cannot grow faster than retail shopping.

Perhaps, this is one of the reasons that this competition starts even at the kindergarten level. Every little bit helps.

She mentions that the Chinese government acknowledges this problem, and is trying to deal with it using a top-down approach, but so far all the attempts to curb the tsunami have largely been limited in success.

This unbearable competition imposes a colossal strain on human conscience, and, naturally people are imperfect, and they start to cheat. In fact, they cheat on a massive scale.

1.5. Cheating

She spends a large amount of effort do describe the amount of corruption permeating Chinese society.

Everyone pays for everything to everyone. She, first and foremost, sees corruption at school, but it is far from the only area of life soaked in corruption.

(Here I have to interrupt myself and refer to another book broadly attributed to the “Chinese domain” in my reading – the “China’s Gilded Age”, by Yuen Yuen Ang.)

What cannot be expressed in raw cash is expressed in services, access to people and gifts.

She spends a large amount of ink describing Chinese obsession with Western brands of clothing and accessories. I couldn’t prevent myself from seeing Western arrogance in her attitude.

For me it was not surprising at all to see the people with less exposure to marketing and advertisement to be much more pliable to the magic of the brand names and the prestige of the price. “The Westerners” do it this way → “The Westerners” are successful → We need to do it this way, it is the right way.

It is, perhaps, ironic that people who are so skillful at cheating are, at the same time, so vulnerable to cheating themselves. And it is also ironic that Chu does not see the whole concept of branding as cheating, although it clearly is. “Apple” products are not called “Foxconn”, although that would have been earnest.

1.6. Militarism

The books does not bear the word “Soldiers” in its title for nothing.

She uses “soldiers” as a metaphor to describe the atmosphere in the kindergarten her son was visiting, and broadly to describe the atmosphere in the educational institutions in general.

This was, perhaps, the thing from the book, I could relate with to the greatest extent.

Russian school culture is also borrowing a lot from the army culture. Maybe this is a thing that the Chinese have borrowed from the USSR, and considered useful. Or, maybe, it penetrated Russian and Chinese cultures independently, coming from Germany (Prussia? Bismarck?). Is there even a realistic way to build a nation without resorting to some sort of military surrogates? (Even democracies have Scouts and invest a lot in sport.)

At Alexander Auzan’s lectures on institutional economics, I heard “School, Prison, and Army build nations”. I kept recalling this phrase while reading the book.

I am entirely ignorant about Chinese prisons; (Although for the interested, there is a Magazeta podcast about that.), but the schools and the army certainly do their share in what is modern China.

Mrs Chu believes, that Chinese militarism disappears as swiftly as it appears, when the “Little Soldiers” grow up and start understanding a little more about the world around them. However, the pictures of her boy marching along the flat corridor were very vivid, and we should not forget that she went to the most prestigious kindergarten in Shanghai.

I remember that in Russia we also had schools that were particularly keen on “militaristic patriotism”, and one of my schools was “leaning towards” that.

1.7. Migration and overpopulation

China seems to suffer from overpopulation in “Little Soldiers”. In fact, quite a lot of grievances outlined in the book she attributes to overpopulation.

People have to become migrant workers in big cities, due to the lack of opportunities at home. Women have to become prostitutes, for similar reasons.

Corruption is largely due to the overpopulation and lack of teachers. And the overwhelming reverence before teachers also comes from the fact that teachers are just too few.

And while I have seen quite a lot of it with my own eyes, sometimes I wonder which is the cause, and which is the effect. After all, China comparable in both size and budget with Europe if taken as a whole.

However, I am feeling that this is not all of the picture. After all, people are not as eager to have children nowadays, as they used to be in the past. Moreover, with such a giant business opportunity, it is strange that business has not found a solution.

1.8. Shanghai

In any case, the love to Shanghai is permeating the book from the first page to the last. And I completely understand! At least for me, Shanghai was a place that I fell in love with very quickly.

And, honestly, I am quite happy that there are other people who are feeling the same.

Although I have not actually managed to recognise the school that played such a major role in the plot, I have been in contact with a bit of the Chinese education system, and I can very well relate to what she is writing about.

And even so, Shanghai is a lovely place, which is full of marvels, and unexpected discoveries.

Thank you very much, Mrs Chu, for bringing this up once again.

1.9. Epilogue

This review happened to be written in a much more disorganised way than my previous ones. This is a little strange, since this book is supposed to be much easier than most of the previous ones I have written the review for. It is not advanced tech, and not even rigorous science, and was, frankly, an easy listen. (Yes, I have listened to it using the Text-To-Speech machinery, as I do quite a lot of my books.)

Do I recommend reading it? Definitely! It should take no more than a couple of evenings, if reading from paper.

It would be a ton of fun for anyone who is into China, into Shanghai, into education, or is just raising his own child.

Shall it be included in the High School Curriculum? I guess, my life could have gone a different way if I had read this book as a school student. Hence, it is very unlikely that anybody is going to let such a book be studied at school. After all, teachers are depicted there as ordinary human beings, and that is one offence a school would never forgive. But, if you are a high-school student, and you happen to be passing by this review, by all means, taste it. You will get plenty of examples to taunt your teachers and become their chief nuisance.

For everyone interested in China, this is also a really nice exposition into the “real” China.

1.10. Contacts

Subscribe and donate if you find anything in this blog and/or other pages useful. Repost, share and discuss, feedback helps me become better.

I also have:

- http://facebook.com/vladimir.nikishkin

- Telegram

- http://t.me/unobvious

- GitLab

- http://gitlab.com/lockywolf

- https://twitter.com/VANikishkin

- PayPal

- https://paypal.me/independentresearch