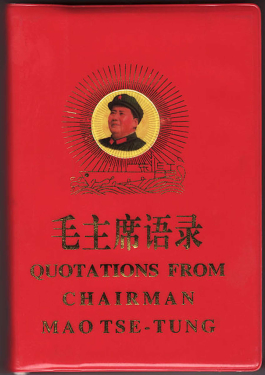

Reading “Quotations of Chairman Mao Zedong”.

I suspect that most readers of my notes have heard about the book called “Quotations of Chairman Mao Zedong”. (It is often translated into English using the Wade-Giles latinization Mao Tse-Tung, because it was published during the times when PinYin had not yet become an indisputable standard.)

It is one of the most published books in the world, and it is likely that if you have seen one of those little red pocket books, it has probably been one of the double-language editions, with odd pages bearing a Chinese text, and even pages loaded with English, Russian, French, or some other word language, depending on which target audience the book was aiming for.

Curiously, you won’t really elicit the feeling of familiarity if you show this book to a Chinese person. The Chinese are usually amazed by the fact that you are so interested in either China or Communism, and are genuinely fascinated by the fact that you have a pocket version of the book, as if you are that much of an aficionado that you just have to carry the source of truth close to yourself all the time. However, native Chinese are much more familiar with “Selected Works of Chairman Mao” (dubbed Mao Xuan), or even “Complete Works of Chairman Mao”. Nothing like the commonly imagined image of a young revolutionary holding the book close to the heart while storming the barricades. Why so?

It was published during the times when Chinese Communism was still aiming at strictly following the internationalist agenda of the original Marxist thought. The “Little Red Book” is an export version, a tool designed for conquering foreign thought rather than for routing Chinese population.

As a result, I would recommend reading the “Little Red Book” as a way of learning Chinese more than as a way of learning about China or Communism. However, as a way of learning Chinese it is really an excellent book.

It is really a book of quotations, or rather short passages of thought dedicated to certain topics, extracted from a set of canonical papers produced by Chairman Mao Zedong since 1920s, and until about 1965. Most quotations are not pithy witty phrases, but rather small passages of several sentences, each dedicated to a certain thought, readable by a dedicated student in 10 minutes, and having a judicious amount of idioms, enough to prevent boredom, but not to overwhelm with metaphors.

Quotations are grouped by topics, so can be consulted without reading the whole text. Some of the quotations, no too many, end up being reprinted in several topics, which is actually better than one might think, because, again, it is best to see the books as a textbook on Chinese language, and repetition is the mother of learning.

I have read the book with a pencil, circling difficult phrases and expressions, and working through them with my teacher on face-to-face classes, which ended up being a very efficient way of learning: I had a guide book, I had a way to resolve questions too difficult to get through myself, and the broad variety of topics allowed me to get distracted from the text when I got tired and interrogate my teacher about the words and phrases used in the context of the topics by ordinary Chinese people in daily life.

I might be a little biased in this respect, as a Russian, because quite a few expressions from the books ended up being familiar to me just because of the childhood exposure to the Communist context, the expressions such as “dialectic materialism”, “democratic centralism”, “reactionary cliques” and “collective property rights”. It might sound a bit outdated nowadays, but, at the end of the day, the works of political economists might get outdated, but they do so by being superseded by the works of newer philosophers and economists working in the same fields, so most of the language still ends up being very useful.

Despite having a few outdated constructions, the language is vivid and thrilling, and really makes the reader imagine the events happening behind the scenes: Chairman Mao in the 20s, fighting a revolutionary war with the warlords, Chairman Mao in the 40s, fighting the Japanese, Chairman Mao in the 50s, now the leader of all of China, considering the internal and external political questions of China.

A large part of the book is dedicated to building the Communist party as an organization, but if one uses a bunch of stickers to cover the word “party”, it would make a rich set of solid advice on building any set of social organizations: companies, teams, clubs, anything. Chairman Mao is very savvy at building organizations, and very observant of the issues which definitely arise when doing it, so learning from his experience is a very useful tool of becoming socially skilled. Not everything he is saying can be blindly applied nowadays, but his observations on the interaction of theory and practice certainly deserve a place on the bookshelf of a practical researcher.

Overall, I do recommend reading the book, perhaps in translation, if you are not interested in learning Chinese, even though the books would lose a bit of its atmosphere in translation.