Reading “Democracy: The God That Failed” by Hans-Hermann Hoppe.

I have read “Democracy: The God That Failed” by Hans-Hermann Hoppe.

Initially, I thought that it would be deep, thoughtful reading, similar to that required to comprehend at least the “Managerial Revolution”, if not “The Capital” or “Wealth of Nations”. In fact, the book is very light on mathematics and, even though it presents a general introduction into the Austrian economic school political stance, it does not even try to be scientifically rigorous.

In this “review” I want to write down what I remember from the book, for my own future reference.

I admit that I had had certain pre-conceptions before starting to read the book, and several of those happened to be false. Of course I knew that the Austrian school stands in opposition to Marxism, but I did not know how exactly it does so. I chose to read Hoppe’s “Democracy: The God That Failed” because I had a vague idea about the “school” development, with three main figures being well-known: Ludwig von Mises, Murray Rothbard, and Hans-Hermann Hoppe, each of them being a spiritual successor of the previous one, and Hoppe being the youngest of them, and still alive.

If you are interested in what I managed to read out of it, you’re welcome under the cut.

1. Body

1.1. What is “Austrian Economics”

- Marxism

- Data and evidence

- Axiomatic approach

For those readers who care little about the book itself, and just came her looking for a layman summary of Austrian school of Economics, go no further, this section is the only one you need to read.

Austrian School of Economics was founded, indeed, in Austria, but not by its most famous nowadays representative Ludwig von Mises, but by Carl Menger, to whose work “Principles of Economics” I probably should refer anyone willing to read the sources. This work was released in 1871, 6 years after the first volume of “Das Kapital”, but before the last volume was published, and, of course, 23 years after the “Communist Manifesto” was published.

Until then, the dominant theory of value in economics had been the “cost-of-production” theory of value. This theory, created by Adam Smith around year 1760, can roughly be summarised in the following way: “the value of a product is the sum of values of its constituent parts”. To be more precise, “labour”, invested in creation of the product, is also its constituent part. What immediately follows from this “definition” is that the value of a batch of goods is the sum of the values of the individual goods contained in that batch. (Hence if manufacturing a bigger batch has the same “fixed costs” as is manufacturing a small batch, then bigger batches are strictly better than smaller batches.) The same theory was further developed by Karl Marx, who, despite being a strict opponent of Capitalism, already firmly associated with Smith, fundamentally supported the same basic definition of value.

One important thing to mention here is that “value” is not the same thing as “price”. While “price” is more or less a well-defined number, usually represented in money (but not always), “value” requires some a-priori psychological definition. Smith was aware of this and this is why he actually started his economic studies from a theory of morality, not from the theory of capital, in the book “Theory of Moral Sentiments”. (The book came out in 1776, when the USA was not yet independent from Great Britan.) Marx and Engels, on the other had, are opposed to this view! In some sense they are more Capitalist than Smith, as their moral theory of value comes after their monetary theory of value. (The book is called “On the Origins of Family, Private Property, and the State”, and was released in 1884.)

Yet in 1871 a certain Carl Menger is not satisfied with the cost-of-production theory of value. Stated informally, his objection rests in that this literally means that we are measuring produced work by tiredness of the labourers. The two most obvious counter-examples to the cost-of-production theory are encapsulated into the phrases “you cannot load money into a gun” or “you cannot eat money”. Indeed, Menger argued, “value” can be created just by selling a product by someone who does not need it to someone who does, since for the first one it is in some sense more of a liability than a value, and the second one really needs it. Moreover, no matter how subjective value (or utility) is, it is clearly strongly non-linear, and moreover, not even strictly positive. Imagine someone eating a vitamin: small amounts can be life-saving, like in the case of scurvy, whereas large amounts can be lethal.

More radical strands of Austrian school (defined here as Menger’s followers) go even further in rejecting cost-of-production theory of value, they claim that it isn’t just not linear but also mathematically indescribable. From here starts a long and painstaking struggle of Austrian school with objective measures, data, and mathematics.

Some more vulgar interpretations of Austrian theses claim that Austrian economists totally reject any econometric methods in the study of economics, but this would be a gross overstatement. The largest counter-example to this overly imprecise claim are the works of Abraham Wald, who was a PhD student of Menger himself, and likely most known to the readers of this blog for “Wald’s identity” in the theory of random processes, who introduced rigorous mathematics to economics.

Not many people know that Wald is actually the person behind the meme picture of a bomber plane with pockmarked wings, illustrative of the “Survivorship bias”. In the Russian context it is more known as an anecdote about dolphins pushing drowning swimmers toward the seashore, presumably helping them to survive; the problem is that those who were pushed in the opposite direction never survived and hence could not tell how dolphins (potentially) caused their demise. This meme represents a fundamental stance of Austrian economic school with respect to data: “correlation is not causation”. That is, data can be used to refute a cause-and-effect hypothesis, but not to prove it.

How would value be determined then, if not on the basis of any solid model? The answer is then: experimentally and politically, through the process of negotiation, bargaining, and trading. From this basic premise, however, Austrian economists make quite an overarching conclusion that in order to determine the value of a good, the bargaining process must be as unrestricted as possible (the First Premise of Austrian economic school). There is the Second Premise as well: private property is sacrosanct, because otherwise bargaining would not make much sense. It is important to note that the theory of “bounded rationality”, as it is known in modern economics (especially the Institutionalist paradigm) and “computational complexity”, as it is known in Computer Science, would likely play a large role in trying to model at least roughly the value preferences of agents.

Menger also had a theory of money where he discussed the relative advantages of gold and silver coins as a medium of exchange concluding that no other available medium of exchange can really compare with them, a premise that the Austrian economic school still holds until today.

The Austrian school was growing in Austria after Carl Menger for many years. The critique and the attempts to disprove Marx played a large role in their studies. Curiously, it can be argued that they were Popperians before Popper, who unfolded his crusade against “historicism” in 1944. Curiously, Popper is not traditionally attributed to the Austrian school, even though he studied in Vienna and was opposed to Marxism on, basically, the same premises: an unfalsifiable theory which cannot be verified or falsified on the basis of historical data.

In the 1930s, Europe saw many transformations, in particular, Germany was building its empire, persecuting inconvenient scientists, and after Austria became a part of Germany, the same phenomena unfolded in Austria too. At that time, one prominent member of the Austrian economic school was Ludwig von Mises. Even people who know nothing about the economic and mathematics of the Austrian school have a chance of hearing surname “Mises”, either as a part of “Mises Institute” in political news, or as “Cramer-von-Mises test” in statistics. The Mises of the Mises Institute is the same Mises, whereas Mises the statistician is not the same Mises the person, but it is the same Mises the surname, it is Ludwig von Mises’ brother, Richard von Mises. By the way, Mises’s mother’ maternal name had been Landau.

Mises is the second or third most prominent figure in the Austrian school, after Menger. Mises is famous for formulating the “Action axiom”, that is, “an action will be taken if its expected utility will be positive”. (What if our agent cannot compute that utility?) Mises is also known for extensively working on the theory of money, continuing to support Menger in that silver and gold are still the best exchange methods, arisen through evolution, but he also spent effort describing why other exchange methods are inferior. He taught at NYU.

Since Ludwig von Mises the story of the Austrian school splits into two branches: the one symbolised by Friedrich von Hayek, a colleague of Mises in Vienna in the 1920s, and sometimes called the Chicago branch, because Hayek, after leaving his mark on the London School of Economics, later moved to Chicago; and the one associated with Murray Rothbard, who was the first prominent Austrian school economist born and educated in the USA. Even though in the later part of the 20th century Hayek won the Nobel Prize and thus revived public interest to the Austrian school, in this introduction I do not have much to say about this branch due to space constraints and insufficient knowledge.

Rothbard studied mathematics, later economics, and got acquainted with Ludwig von Mises in 1950, when Mises was already living in the USA. Rather productive, he wrote more than 10 books, most of which deal with refuting mainstream economic theories as overfit models based on survivorship bias. Instead of applying “scientific method” and econometrics to the study of human value-maximising actions (economy), he promoted the use of Mises’ “praxeology”, which is a mathematical in spirit (rather than physicalist in spirit, Marxist) approach to economics.

Rothbard was active politically, which is a fairly logical consequence of rejecting “strict” academism, and where he surprisingly converges with the “New Left” academics such as Judith Butler, ironically. As a result of his work, several journals, academic institutions, and political movements were founded or heavily influenced, including Centre for Libertarian Studies, Cato Institute, Mises Institute, Libertarian Party USA. He was a friend, and at the same time a bitter rival of Ayn Rand whom he admired for the ability to promote Libertarianism among the common fork, but bitterly ridiculed for her economic misconceptions and vulgar understanding of “natural order”.

There are much more Austrian school economists and economic theories to discuss, but I want to conclude this brief introduction with the author of the book I wanted to review in this essay, Hans-Hermann Hoppe. Hoppe was born and educated in FRG, and to this day is, despite his extensive connection to the USA, a European economist. He worked for the Mises institute, was on friendly terms with Rothbard, and is still considered a leading figure in the Mises branch of the Austrian school, even though nowadays he is developing his own social movement called “Property and Freedom Society” and is based primarily in Turkey.

In a few words, Hoppe has developed and deepened the economic-political theory of Rothbard, leading it to its logical conclusion, a vaguely masqueraded monarchy. Admittedly, it’s not entirely a monarchy, it has certain unique traits, but roughly speaking, still a monarchy. This is where he is different from Rothbard and all the previous Austrian school economists. Even though they were already sceptical about democracy and universal suffrage, none of them had actual courage to proclaim that the whole paradigm of the world’s social evolution as “progress” is misleading. He has wrote several works, but this one, “Democracy: The God that Failed”, is probably the most famous and aimed at the widest audience, ready to be used as an introductory reading.

1.2. What is the book about

Returning a little bit to the beginning of the review, and re-considering the Marxist theory of value, we can easily see how the idea of (social) progress has become one of the foundational, and, indeed, one of the most attractive properties of Marxism.

If we believe in the cost-of-production theory of value, then the larger the production, the more “civilised” is the society, because with constant “fixed costs” the price of each individual “good” is reduced, and hence the “social progress”, the process of civilisation, naturally becomes a process of scaling production. Hence the evolution of social stages: prehistoric society, slave-owner society, feudalism, capitalism, communism is largely the process of creating the more and more scale in production, and the more and more complex systems. The theory of exploitation stems from the same basic premise: if the only “added value” introduced into a more complex product besides the values of its constituents is the labour cost, then the capitalist, who is owning the means of production, is not adding any value into the production process, is a parasite.

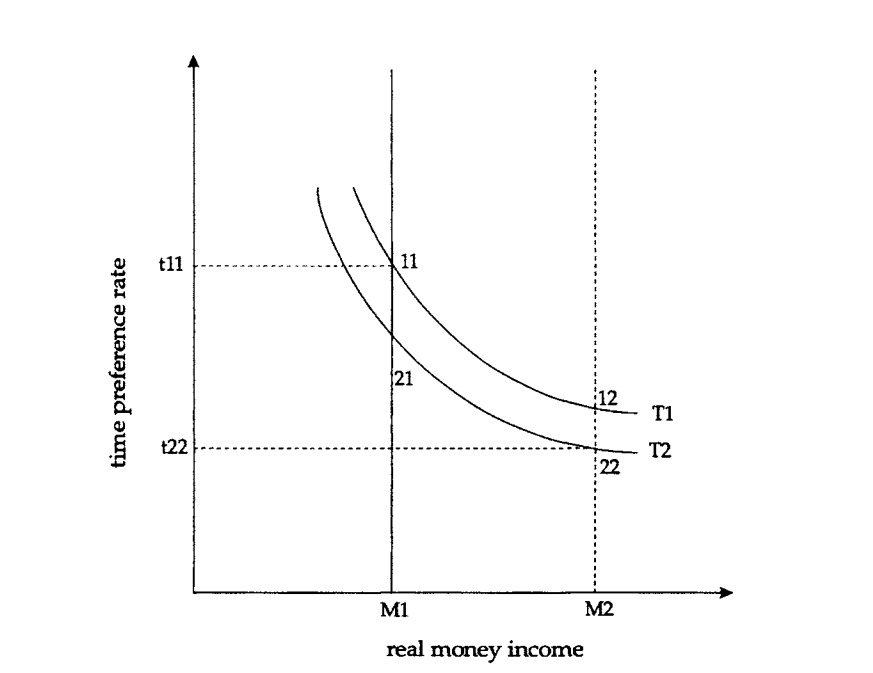

The book does not mention it, and it is a big drawback of the narrative, that even most orthodox schools of economics do not disregard the fact that linear approximation of value from size is a rough approximation. What the book does explain quite in detail is the fact that this “value function” depends not just on size, but also on time. By time dependence they mean not just the actual dependence of the function on time, which can be naively constructed from instant snapshots, but the subjective dependence of a value produced by a good on the time of “maturation” of this good. The dependence of this function from time represents the “planning horizon” of an economic subject. Naturally, most goods are better today than tomorrow (after all, I might not happen to live until tomorrow), but how exactly better? The process of flattening of this curve, broadening the planning horizon and thus encouraging saving and investment is what the Austrian school calls the “civilisation”. (Compare this to the Marxist definition of progress.)

According to this measure, human progress does not at all increase (or decrease) linearly, at least there is nothing fundamental about it increasing. (As we remember, the trajectory, which Mankind has been developing along, and which fits the Marxists definition of progress, the Austrians do not consider to be that progressive.) Indeed, the Austrian school considers the recent 250 years to be exhibiting the process of de-civilisation, that is the retreat of a more civilised monarchist society, where monarchs exercised private property ownership, toward the more primitive collectivist society, more fit to antiquity and the incessant 500 years of Roman republican warfare than to a modern “enlightened” era.

1.3. What are “democracy”, “monarchy”, and “natural order”

Before reading this book I had essentially two models of “social orders” in mind, the Aristotelian basic grouping into: Democracy (the power of the many), Oligarchy (the power of the few), and Monarchy (the power of the one), based on the concentration of power; and the Marxist one, based on the theory of the “ruling class”: Prehistoric, Slave-owner, Feudal, Capitalist (Bourgeois), and Communist (Socialist).

Hoppe’s theory, I would say, is even more self-contradictory than the previously mentioned two, contains the following three: Democracy, Monarchy, and Anarchy, also called Anarcho-Capitalism or Natural Order. I am saying “self-contradictory”, because, really, in spite of claiming that natural order is the superior system, maximising produced value, either I failed to fully grasp the true difference between Monarchy and Natural Order, or Hoppe failed to explain it in sufficient detail.

1.3.1. Natural Order

I will start from presenting Natural Order, as the definition of it is likely to be the most novel thing for the readers, in spite of having the word “Natural” in it.

I will try to present it here as faithfully as I understand, but bear in mind that I might be mistaken.

So, as far as I understand, An-Cap is just like Monarchy, but the monopoly of violence on a certain territory is leased from a private military company (called an Insurance Company in the book) instead of being organised by the owner of territory himself. That is, the monopoly of violence on a private property is still upheld, but the use and the provision of the said violence are separated into different legal entities. That is, it is, seemingly, expected that the private property where the Insurance Company ordinarily stockpiles means of war, such as weapons and soldiers is relatively minor, unlike the area which countries, even monarchical, occupy, but private land-owners are expected to lease their, highly mobile, forces to provide protection on their own land. The reason why an Insurance Company is unlikely to cease the land from the land-owners and employ it for personal use and extraction of wealth by the means of taxes is essentially that managing estates is more burdensome and less profitable than charging an agreed fee for services.

It seems that Hoppe expects that fatal violence, that is people ending up dead in struggles is considered low, at least, he expects, most offenders will be expelled rather than killed in the process of reaffirming the rights of property owners. However, since he expects that most of the nice land is going to be occupied by people unwilling to accept criminals, as far as I understand “expulsions” making people end up on a No-Man’s-Land in Antarctica or Western Sahara are likely to become fatal very quickly.

It should be noted that many premises of the Natural Order are demanding a fairly high degree of consciousness from the people participating in it, but Hoppe is not at all discouraged by this fact, presumably because during the course of history people have been seen to believe in a broad variety of different things, ranging from self-evident to us nowadays to completely wild, so he is not finding it unnatural that at some point the “unnatural beliefs” may disappear, as being a meta-stable fluctuation of a stochastic system of human collective subconscious. Indeed, throughout the books he repeatedly stresses the importance of “public opinion” to the stability and power of the Government, whether monarchical or republican, and generally projects a feeling that the formal procedures which accompany more or less every regime, whether ceremonies (crowning, anointment) in a monarchy, or bureaucratic processes (elections, constitutional conventions), are merely theatre, which exists to obscure the main mechanisms of power, and not to expose them. “Indeed”, he says, “if elections do not exist, the natural way to remove a misbehaving politician from power is a coup or an uprising. No would you expect a politician considering ill policies to be more afraid of losing an election, or of getting killed?”

He does not mention which regimes actually ever implemented “Natural Order”, but in his writings he is the most sympathetic to Switzerland and the 13 Colonies before the Constitution (and perhaps even before the Declaration of Independence, but I am not very sure).

1.3.2. Democracy versus Monarchy

He is admitting that “Natural Order” does not really exist in the world at the moment, but from among the regimes available to study empirically, he self-evidently prefers monarchies, and spends a great effort on illustrating why.

He admits that not all monarchies and not all democracies are the same, but to him it is very self-evident that as the amount of democracy (collective ownership) in a country increases, all the negative effects of the government onto its people also increase

- Taxes

- Debts

- Inflation

- Crime and domestic violence

- Militarism abroad

- Tariffs

The first two phenomena, without the negative connotation assigned to them by the Austrian school, are even more or less universally admitted by most economic schools. Indeed, the amount of taxation imposed by monarchs onto the subjects was most often targeted rather than universal, such as “money required for a certain construction project” or “money required for conducting war”. He does not mention either the Church tax, or the Feudal corvée labour, presumably assigning them to private agreements between voluntary participants? But on the face of it, indeed, government’s taxes rarely exceeded 3% of GDP in monarchical societies, and of those 75% were spent on the army, this is a historic fact.

The question of inflation is more nuanced. The Austrian school is firmly opposed to fiat currencies and supports a gold/silver standard, arguing that gold is a nice and convenient way of conducting exchange, given that it is portable, infinitely divisible, has its intrinsic value used for the production of jewellery and fine machinery, so keeps being worth something even when overproduced. He presents no opinion on Blockchain, and no opinion on a more interesting to me “petrol-backed monetary standard” or Pereslegin’s “kilowatt-hour-backed monetary standard”, but at least paper money for him are big no-no. He does not mention the fact that the Romans before Diocletian were hugely suffering from inflation, while, faithfully to the Austrian economic school, maintaining the silver and gold cons as the main payment instrument. It is also worth mentioning that, as most Russian readers of Yevheni Onegin know, corvée labour was only replaced by payments in cash in the 19th century, and I suspect that largely not that much due to the lack of banking, but due to the fact that most peasants could not count to ten, and very little produce was actually sold on the markets, but, again, for the Austrian school, correlation does not equal causation.

Statistics on crime, policing, and social order are very hard to equalise for the societies in different historic periods, so I will not be discussing his logic in detail.

With respect to militarism and foreign interventionism, most people agree that mass mobilisation armies of the 19th century were what made the rise of nationalism possible, and what transformed War from an aristocratic game into the total genocidal war of nations. This seems to agree with the facts (even though correlation does not equal causation), however it should be noted that it is not clear how this relates to the spread of universal literacy and with devastating wars of the old times, such as the 30-years war, the War of Spanish Succession, and the genocide of Picts by Septimus Severus. Presumably they will, as usual, say that the few fluctuations to not disprove a general rule in social sciences. In any case, Hoppe’s references to the relative restraint found in monarchical warfare is reinforced by several books he refers the interested readers to. Generally, the book is very well sourced with references and quotations, several chapters having as many as 50.

But the most horrendous phenomenon exhibited by the democratic regimes compared to the monarchical ones the low planning horizon and the easy permeability of the government offices to riff-raff. He is claiming that these two characteristics almost guarantee poor government, even if the government manages to stay in power as long as a monarch. When a government shareholder, say, a president is in power, it is in his best interest to abuse power as quickly and as strongly as possible, to maximise his own wealth. Even if he manages to get re-elected, the risk of losing the next election is always with him. For the government employees and the common folk, the temptation is similar, although distinct. While government employees are not usually laid off after an election, they are still infinitely tempted by promotion and getting access to greater riches, so are interested in maximising their career perspectives, and not in doing their job the best, and the common folk are always tempted to become a part of the government, and by the government allocating for them more and more wealth. All these traits, argues Hoppe, are detrimental to the length of the planning horizon.

While he admits that the nobility and the king in a monarchy are prone to all the same temptations, he believes that the degree is much lower, and moreover, since the ruling pyramid levels are impenetrable, the class interests (in Marxist terms) switch from becoming a ruling class to protecting their own rights. He says that voluntary associations are much more likely to occur between cooperating people when in-voluntary associations (such as being attributed to a group or class according to the government’s law) are minimal.

It seems to me that a lot of his arguments against democracy are very similar to Aristotle’s.

1.4. Relationship of an-capists to liberals, minarchists, and conservatives

A noteworthy part of the book is dedicated to the discussion of the competing political groups and movements.

He discusses:

- Liberal-Democrats,

- Conservatives,

- Libertarians.

Curiously absent are the classical Soviet-style socialists, perhaps because by the time of writing of the book the Soviet union had been already dead for 10 years.

With respect to Liberal-Democrats (Democratic Socialists), Hoppe says that their main issue is that they are too shy of being true Communists. In fact, he says that Liberalism as designed by Locke is an incomplete theory. It is based on the premise that the State is a monopolistic provider of protection, and that protection is the only resource which is better when provided by a single supplier. Both of those premises, says Hoppe, are false. As I have already mentioned when describing Hoppe’s theory of Natural Order and Insurance Companies he does not see competitive provision of security services as impossible, whereas the main problem with Liberalism per se is that it is unclear what should be the limits of protection provided by the government.

Clearly in the days of Locke it was protection against foreign military invasions, but this is just a historical coincidence and the result of the overall prevalence of monarchies in the world. But ordinary untrained people are not just unfit for the production of protection from foreign armies, he says. People are just as equally unfit to protect themselves against health issues, ageing, discrimination, and a lot of other things. Hence people who are voting in an election, are expected for vote for more and more “protections” from the government, until the government bankrupts the country.

With respect to Conservatives he is saying that while conservatives are generally well intended, their main issues are that they still support a big government, even with less resources, still support democracy, and, frankly speaking, do not really know what they are exactly trying to “conserve” because none of them were alive when monarchies were omnipresent. Overall, Conservatism is a reactive ideology, not pro-active, therefore is always expected to be on the losing side. As to their “social conservatism”, he is fully on board it, except that it should be voluntarily accepted on private properties, not imposed by a law, however, he has little doubt that this will be the case, as most people are conservatives in the heart, and are corrupted by Socialism. He is sarcastically derides the Conservative establishment though, calling them National-Socialists, so he is aiming more at cannibalising their movement rather than at making an alliance.

With respect to Libertarians he is even more derisive. The Libertarian Party is still democratic in spirit, which has largely stood on the “socially liberal, economically liberal” position, and it is more often associated with the Cato Institute and “Minarchist” (that is, not An-Cap) libertarians. While their intentions are good, says Hoppe, they fundamentally do not reject democracy, which to him is a major problem, and, from a practical perspective, they have become an attractor for asocial elements, freaks, people with pink hair, and similarly socially maladjusted people, and hence are unlikely to ever get successful in implementing their programme. He is also very sceptical about people promoting free movement of people analogously to the free movement of goods, but on this see later.

1.5. How to reach an-cap

Discussing how Anarcho-Capitalism can be established at least somewhere, we should recall that Hoppe and An-Cap Austrian economists highly value public opinion and disregard elections, democracy, and bureaucracy. Therefore, there is no “political party” at whose numbers we can have a look and determine their success or failure.

Moreover, since they are sceptical about “public debate” and “social mobility”, it is logical that these people would be very likely to try and participate in “non-public politics”, “politics with non-political means”, and hidden subversion. In such a case it is not at all easy to assess their success from the outside.

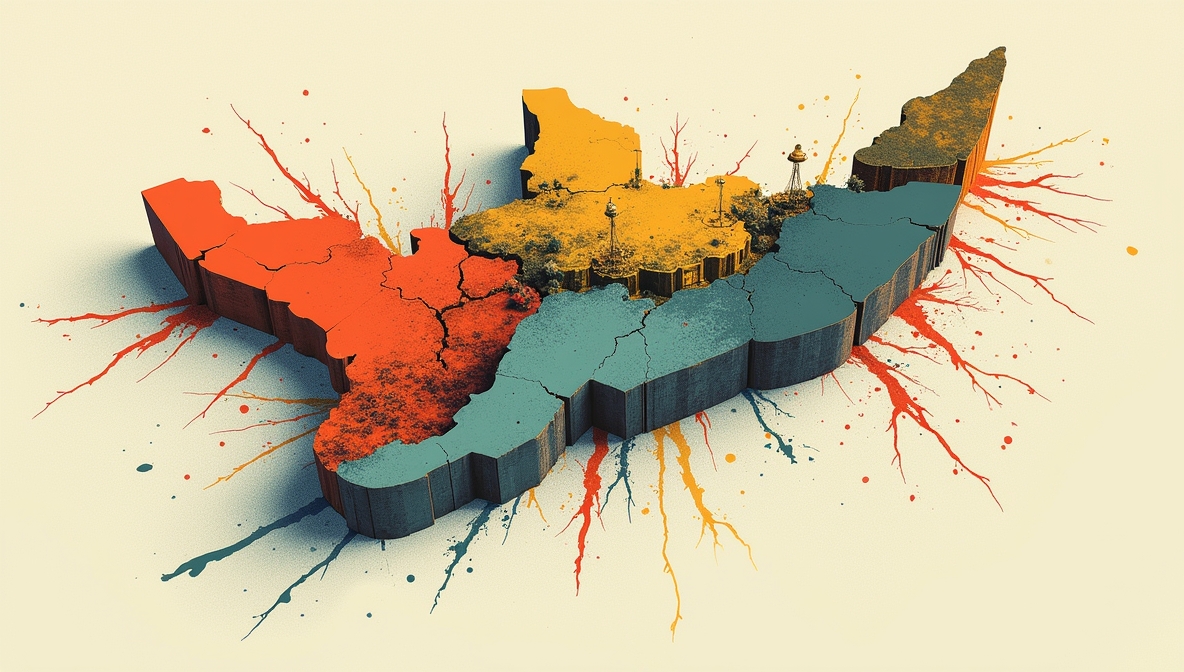

As to what Hoppe is saying openly about the political competition, it is as follows; the best examples of the “seeds of An-Cap” are micro-nations which already exist on Earth: Hong Kong (formerly), Singapore, Monaco, Luxembourg, Lichtenstein, San-Marino, Andorra, and to lesser extent, Switzerland and UAE. He is generally saying that the most efficient way to invest one’s political resources is the local level, and the investment should be aimed at promoting cultural disunity and political secessionism.

That is, rather than having a revolution in the whole country, what is desired is having those big countries be torn apart into myriads of tiny independent city-state, which would have to trade using gold as a medium of exchange, because they would not be able to agree on a single fiat currency, and would generally hate each other so much that migration would be unlikely.

1.6. On City, Village, and how they work with An-Cap

It is fun that Hoppe seem quite sceptical Roman roads and bridges, because, even though they facilitate trade, they also incentivise invasions.

Overall, he supports villages and towns in their opposition to big cities, claiming that big cities naturally promote collective ownership, which is evil.

Overall, while he is a big proponent of trade of goods, he is very sceptical about human migration. The point being that goods do not have their own willpower and decision-making (see the Action Axiom by Mises), while people do. He considers letting people enter some territory without a unanimous agreement of all of the owners to be equal to an invasion. (Again, private property on land.) The only case for which he can make an exception is when somebody is inviting the person to come, and is fully responsible for every action of that person in all civil and criminal cases.

This position sounds almost as if it supports slavery, but I do not think this is intentional, this serves rather as a reduction ad absurdum.

He does not oppose migration by buying and selling land though. That is, if someone sells a piece of land, and someone buys a piece of land, he can, obviously, come, as long as his neighbours would let him pass over their territory.

Overall, Hoppe is very critical to the very idea of cities and large urban centres, which, in my opinion, is a great defect in his theory. Perhaps, the libertarian theory of a City is still to be developed.

If all this sounds anti-egalitarian, that is because it is anti-egalitarian. Hoppe repeatedly emphasises the importance of distinctness between people, groups, clans, families, voluntary associations, being them religious, cultural, linguistic, or productive, stressing that fundamental distinction between sexes is the most fundamental basis for cooperation, and he extends this model further – the division of labour only makes sense if people are different, and the more different they are, the more varied tasks they can perform, and the more cooperation is needed. To be honest, the way “cooperation” is justified is just completely wrong from the biological perspective, when speaking about non-human species. In particular, he does not seem to be aware of symbiotic relationships, and disregards voluntary and coercive cooperation between high primates.

Throughout all of the book, he stresses that the main de-civilising force is forced integration. The term “forced integration” is even more prominent than the term “forced expropriation”, and presumably more sinister.

1.7. How courts will work with An-Cap

This section is not really concerned with the book, but I had heard this question said in a sarcastic manner, so I started to wonder myself.

So, answering this question we should first recall that An-Cap is essentially a Monarchy with minor tweaks.

In a Monarchy, the supreme right to decide what is right and wrong on his private land belongs to a monarch, that is to the land owner. So, if you are present on someone else’s land, you have to read in advance, how exactly that person organises justice. Most likely, this person pays an Insurance Company for policing services, and this police look more or less like everyday private security firm employees you can see guarding office buildings, it is easy to recognise them. Therefore, the laws on his land consist of his own demands and the demands of the Insurance Company. If you misbehave or somebody else misbehave, probably the first place to raise concerns is that private police, which will likely either sort out the case according to the Insurance Company regulations, or bring you to the court, organised and funded by the property owner. This court will likely be quick and simple, to save money and effort, and most likely not include the most in-depth investigation, however you are also unlikely to get a huge sentence there, you (or the perpetrator) will likely get an expulsion, and a huge fine. This fine will be extracted via an Insurance Company to Insurance Company negotiation, which might happen to be violent, but unlikely to be so.

This is the simplest case. The jurisdiction might happen to be a Catholic or Muslim, or with some other unorthodox rules, but, as far as I understand, still would not imply capital punishment.

Another story is what happens when two land owners have a conflict among them, each being physically present on their own land. In this case, if they employ the same Insurance Company, the company probably has arbitration rules, and you have to follow them and cannot appeal. If your Companies are different, they would have an arbitration mechanism among themselves, which would usually be simple, but would imply violence in the most severe case.

1.8. Epilogue, on the USA and Austria

History is a sarcastic bitch. The at the time Crown Price of Austria-Hungary was Rudolf von Hapsburg, who was a student of Carl Menger and could, potentially, reform Austria on the principles of Austrian economic school after ascension. However, due to subjective theory of the value applied to his own life, Rudolf chose to commit suicide together with his lover, a lady 13 years younger, which made Franz Ferdinand the new Crown Prince of Austria, which was in turn killed in Sarajevo, igniting the World War I, and which destroyed Austria, created a lot of resentment in one Austrian painter, and made the USA the dominant world power.

Hoppe speaks a lot about this symbolic competition of Austria and the USA before WWI, in which the USA emerged victorious, and Austria disappeared. Austria was the only European empire with no overseas colonies, consisted out of a large number of not-at-all integrated regions, and was one of the world’s leading producers of culture. Wittgenstein, mentioned on this website a few times, also emerged from that enlightened monarchy broth of ideas which constituted the Ancien Regime in Austria.